An attractor state is a set of outcomes towards which a system can be expected to settle. While end states cannot be predicted, they will tend to converge within certain boundaries also referred to as the ‘basin of attraction’, a kind of imaginary vessel pulling all outcomes towards it. In other words, an attractor state essentially defines what we would consider as ‘normal behaviour’. Yet complex systems could have several different attractor states.

Take for example disease outbreaks. Ebola has been known to surface time and again, usually in central and western Africa. Zaire has witnessed 318 cases in 1976, Sudan had 34 cases in 1979, Gabon 52 in 1994, with Zaire suffering another 315 cases in 1995 (see World Health Organisation’s Ebola factsheet). Overall case numbers have shown three kinds of possible outcomes – many years in which no Ebola cases had been observed at all, a number of years with small outbreaks of a few tens of cases found, and some years with bigger outbreaks reaching the few hundreds. Hence for most of recent history we can think about the pattern of Ebola as set within a certain attractor state of between zero and a few hundred cases. And yet, 2013 saw a completely different outbreak both in terms of its geographical spread and the number of cases identified.

2013 to 2016 saw the most widespread Ebola outbreak in history, with 28,616 registered cases associated with 11,310 deaths. What occurred in 2013 can be described as a transition to a new attractor state – from one of small periodic outbreaks to a state of full blown epidemic. An epidemic behaves differently than an outbreak as the scale of contagion increases exponentially. This would imply that existing negative feedback mechanisms that have previously kept outbreaks in check have subsided (see ‘feedback effects’). These could have related to better transportation and greater connectivity amongst denser communities, allowing the virus to reach across a much wider area than before; or even to mutations in the virus itself. Ironically, a slightly less lethal or slower virus would have been able to spread more effectively. As its human hosts would have more time to continue to interact with more people, the probability of wider infection would increase.

Given the lack of medical treatment, the strategy used to address this devastating Ebola epidemic focused on personal and community isolation, in effect aiming to push the pattern back to its previous attractor state. This strategy proved successful. Current efforts to develop a vaccine could again shift the Ebola system into a new attractor state in which no human outbreaks would be observed at all.

The concept of attractor states can be useful for making sense of social phenomena as well. Take for example modern political spectrums. For most of the 20th Century the political spectrum between ‘left’ and ‘right’ had been defined via the question - who should hold an economy’s ‘Commanding Heights’ - the market or the state? Should the government lead in shaping the economy via taxation, regulation, and government investment? or should market forces be left to their own devices unleashing both creative destruction and wealth creation?

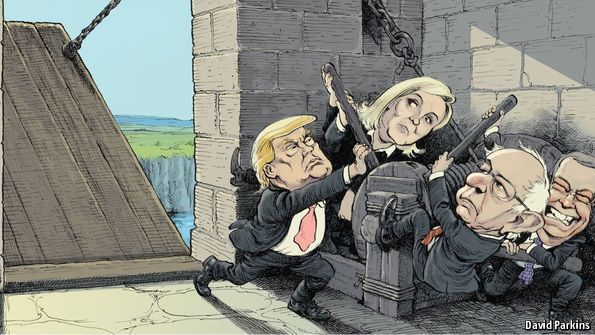

Across the capitalist world this political pendulum seem to continuously swing one way or the other. Take for example the US’s Republicans and Democrats, UK’s Conservatives and Labour, and France’s Republicans and Socialists. They all converge on the same spectrum of ideas, albeit being positioned on different points within it – know the coordinates of one leading political force and you will know the ideological preference of its competitor. And yet some would suggest this political attractor state has now shifted.

The Economist, 2016

The Economist, 2016

For some years now, a new political spectrum has been emerging, only to fully manifest itself in the Brexit and Trump populist shocks of 2016. Described already in 2005 by Stephan Shakespeare, the head of the UKGov polling agency, as the “drawbridge up” vs “drawbridge down”[1] divide, this new political spectrum blurs old ideological boundaries between left and right, while shaping new ones. The fight for our commanding heights has given way to a fight about national borders, immigration, and free trade.

Take Donald Trump as an example, while the worldviews held by traditional American right-wing conservatives adhere to minimising the role of government, he won his candidacy by promising jobs, huge investments in infrastructure, and in effect the curtailment of market competition. His populist counterparts in the UK, and France are similarly mixing and matching old left/right policies and metaphors. Across this new battleground political powers compete over the merits of global integration, with old fashion notions of capitalists vs socialists giving way to localists vs globalists, or as David Goodhart defines them - “the Somewheres vs the Anywheres”[2]. The modern political system has shifted into a new attractor state, a new normal.

SO WHAT does that mean in terms of strategic design?

The most important thing to remember about attractor states is that what we consider as “normal behaviour” or a given spectrum of possibilities, can swiftly change. When analysing the strengths, weaknesses, agendas and interests, both of our own and of our competitors, we tend to assume certain realities as given axioms. These axioms adhere to an existing attractor state. Yet overtime, we may find ourselves playing by old rules and for old gains only within a brand new game.

This could provide one possible explanation for the strategic failures of Israeli and Palestinian peace negotiators. Following the ceremonious signing of the Oslo Accords on the green lawns of the White House in 1993, Israeli and Palestinian leaders have embarked on a decade long negotiation process over the finer details of the ‘Permanent Peace Agreement’. These negotiations assumed a ‘two-state solution’ as an attractor state. In other words, each side assumed that all possible outcomes would end up featuring slightly alternative variations of mutually agreed settings that would allow for two sovereign states to live side by side.

This attractor state was considered by all, including the international community, as the only game in town. They therefore spend valuable time playing hard ball on the finer details of borders, security, and symbolic gestures, focusing on their own hard-lined constituencies, both as a means for legitimacy building and as part of their negotiation tactics. Yet this precious time allowed spoilers on both sides to gradually alter the ground situation, disrupting the system and finally tipping it into a new attractor state. By 2006, the last real ditch at a peace settlement, both sides found themselves with limited powers to push through, not to mention implement a comprehensive two-state agreement. This agreement, with all its fully spelled out variations, annexes, maps, and timelines is sitting in diplomatic drawers all over the world, waiting for the system to tip back.

[1] The Economist, http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21702748-new-divide-rich-countries-not-between-left-and-right-between-open-and

[2] David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere – the populist revolt and the future of politics