4.1 Operationalising Complexity – an introduction

Eric Beinhocker once suggested complexity thinking will only be embraced if it can transform from a Sunday afternoon thought into a Monday morning action, i.e. from complexity thinking to complexity doing[1]. Building Block 2 explored how complexity science provided us with new and deeper understandings of both our natural and human environments, specifically the hidden mechanisms through which natural and social orders emerge, sustain themselves, and transform. From the life cycle of forests to the inner workings of hi-tech clusters, theories of emergence and self-organisation have shed new light on the spontaneous creation of the patterns and structures that surround us. At the same time, our discussion has also suggested the operational limits of this new scientific world view. Unlike the useful articulation of cause-effect relations by its reductionist predecessor, the myriad of interwoven systemic forces as seen through a complexity lens, has to some extent decoupled the traditional link between scientific understanding and prescription for action.

From a decision-maker’s perspective, this seems to have rendered complexity analysis more of an academic than a problem-solving approach. And yet, like Morpheus’s red pill, as one begins to view the richness and dynamism of our world through the lens of complexity, so does it become increasingly hard to square new analytical insights with old reductionist models of action. Hence the question repeatedly asked of complexity experts – how can we bridge the gap between complexity thinking and complexity doing, or in other words, between complex systems that require our understanding, and complex problems that require our actions.

The Cynefin Framework

The Cynefin Framework

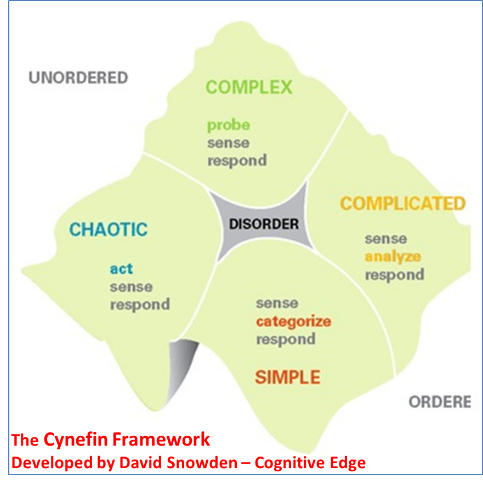

Practitioners have long sought to fill this gap. Dave Snowden for example, drew on Warren Weaver’s typology of scientific endeavours as simple, organized and disorganized complexity[2] to develop the Cynefin framework[3], a simple matrix aimed to help decision makers identify the type of operational context they are dealing with – does it fall under the simple, complicated, chaotic or complex domains? In a simple context cause and effect relations are fully known and certain, this could be as ordinary as a phone running out of battery. Under such circumstances all one needs to do is make sense of the problem, categorise the rather obvious cause-effect relations, and use best practice knowledge to solve it, in this case simply charge the phone.

A complicated problem is not all that different. It also presents a context in which cause and effect relations are knowable and certain. What makes it complicated is the fact that the decision maker might lack the necessary knowledge, or there may be multiple paths towards its solution, in which case calling in the experts is highly recommended. If a phone has been charged but still won’t turn on, one might need to find a technician, or the nearest teenager to help. In other words, complicated problems are all the engineering type problems – from finding the most efficient way to sort and pack Amazon customers’ orders, to building a rocket that can fly to Mars. Even in the realm of rocket science, cause and effect relations are theoretically knowable and certain. Nevertheless, they are also multiple, accumulative, and therefore complicated, making expertise knowledge and past experience crucial in designing new solutions.

The third context decision makers could find themselves in is a chaotic context in which, for all practical purposes, no cause-effect relations exist at all. Certain conditions such as natural disasters occur randomly and in real time do not require immediate in-depth analysis as to their origin. According to Snowden, in such cases decision makers simply need to intuitively react to the situation as it unfolds. This could be as simple as hitting the breaks of a car when a ball suddenly appears in the road ahead, or deploying every available police and army units to help evacuate residents stranded in flooded areas. Educating children to play away from the road, or building better flood defences could only become a relevant challenge in the aftermath. In real time, all that is required is quick and effective intuitive reaction.

It is the forth context of complex problems which is of course the most interesting. In this case, cause and effect relations do exist. Wars, financial crises, political transitions, and relationship breakdowns are not random chaotic events. However, the causes and effects that shape them are multiple, interdependent, and simultaneous, making real time analysis and problem-solving an impossible task. Contrary to the case of complicated contexts, best practice knowledge may not prove helpful. This is because each and every situation, even if highly similar to others, harbours its own unique myriad of effecting forces. Experts might be able to offer better educated guesses, yet these will provide intuitive recommendations at best.

When operating under such circumstances, Snowden suggests decision makers take an adaptive approach - “probe; sense; respond”. At first, some actions are taken in order to test the system’s reaction. Then, the emanating feedbacks are evaluated so as to reveal new information about the system’s conditions. These are then used to inform the design of further iterative actions, and so on and so forth, until conditions are gradually shifted to some new satisfactory state.

Of course, one single event might pose different types of problems for the different decision-makers involved. For example, the 2015 ‘emissions scandal’ which exposed how Volkswagen’s used a “defeat device” to cheat environmental emissions tests, has undoubtedly created a whole range of problems for the different Volkswagen position holders. For the Volkswagen’s engineers it might have been a simple problem of turning the device off; for its aftersales management team it might have created the complicated challenge of recalling eleven million cars for servicing; while for their public relations department it was a chaotic problem requiring quick firefighting reaction. However, for the company’s top management and board, the crisis undoubtedly created the complex challenge of rehabilitating the company’s brand image while trying to minimize its legal liabilities, not to mention the complex personal challenges inevitably experienced by Martin Winterkorn, Volkswagen’s resigning CEO.

Whether a challenge is complex or not depends not only on the specific occurring events but also on the specific context of the decision-maker involved. Nevertheless, if identified as a complex problem best practice cannot serve as a guidance for strategic design. Rather a unique strategy must be developed for the unique and dynamic patterns shaping the problem at hand.

4.2 Established rules of thumb

Snowden’s general recommendations for operating in complex situations, i.e. the need for continuous experimental and adaptive modes of action is a shared theme within the wider “complexity for practitioners” literature. Accompanying it are several other common themes. First, in the words of Nobel laureate Murry Gell-Mann is the need to “take a crude look at the whole”. When operating in a complex environment decision makers should get a sense of the system as a whole before planning any action. Towards this end, a variety of different mapping and simulation methods have been developed. This with the aim of capturing and presenting the multiplicity of players, relations and forces shaping existing conditions within a given system.

Afghanistan Stability

Afghanistan Stability

Such stock taking exercises provide a helpful bird’s eye view of existing conditions and relationships, even though these tend to be presented as they currently are, rather than through their underlying drivers or the manner in which they have emerged. See for example the famous, or rather infamous, Afghanistan Counter Insurgency spaghetti map developed by the US Army. While highly detailed in its description, it hardly cries out operational solutions[4].

Still, while such outputs might seem overwhelming, they can be surprisingly helpful at times in identifying previously hidden relationships. For example, over-grazing has been wrongly associated for many years with desertification. However, a systemic exploration into the feedback dynamics between farming, herding, soil and flora renewal across the world, have actually revealed the positive contribution of herding animals to ecological stability[5]. Previous policies that have tried to restrict the movement of herds, and in some cases even opted for the culling of wild animals could now be overturned.

[6]The ecologist Allen Savory who has lead this doctrinal shift, has since developed a whole new framework for ‘holistic management’. This new approach manages the re-introduction of large grazing herds into what are now barren areas and has been proven to overturn the desertification process in a surprisingly efficient manner.

Las Pilas Ranch

Las Pilas Ranch

At the opposite end to the “crude look at the whole” is a highly-detailed worm’s eye view of the system’s grassroots. As complex systems emerge through a continuous bottom up process by which individual agents interact and adapt to emerging patterns, figuring them out becomes a key operational challenge. Thus, a second key theme found across the complexity discourse is the need to engage ever wider circles of stakeholders. As Snowden’s Cynefin framework suggests, in complex contexts best practice knowledge, such as dispensed by experts, will not necessarily prove relevant under different systemic circumstances. The challenge is always to uncover the unique circumstances shaping a specific system. It therefore becomes necessary to access information that can reveal the deepest local conditions that shape individual choices and actions. This can only be done at the very grassroots level.

In trying to take on the complex challenge of upgrading slums in Santiago Chile, the La Barnechea Social Housing project took a highly participatory approach for optimising design solutions for local needs. Designed by 2016 Pritzker laureate Alejandro Aravena, Houses were given to slum dwellers only half built. Over time, this would allow them to further develop and adapt them according to their own personal needs and financial abilities. This unconventional approach was chosen not only due to the limited funding available in the project, but also due to the crucial understanding that a high fitness solution requires access to local knowledge that only the participants themselves would have. For example, given the budget constraints, new residents were offered a choice between having either a bath or a hot water heater installed. While development and housing experts would generally suggest opting for the hot water, in one hundred percent of the cases residents preferred the bath[7].

This somewhat surprising choice could be explained by the high personal value attached to notions of privacy, an experience so lacking in their old slum dwellings where a shower meant simply using a bucket outside their home. Moreover, when first moving in, they would not have the money to pay the initial electricity bills anyway. Taking the worm’s eye view such preferences make complete sense, yet access to this knowledge is particularly hard to gain, even for experts with years of experience in the development field. One must live the system in order to be able to explain it. Incidentally, Alejandro Aravena has now made four of his social housing designs free to the public for open source use[8].

Alejandro Aravena’s Designs

Alejandro Aravena’s Designs

Mining local knowledge for highly fitting solutions has been similarly used in tackling other complex challenges such as malnutrition. In some cases, it was not only about identifying local information but also about using the natural dynamics of complex systems to promote systemic change. Complexity related concepts such as ‘positive deviance’ discussed in Ben Ramlingham critique of the economic development industry[9], build on identifying successful outliers for problematic systemic patterns so as to try and uncover, rather than invent, new strategies. For example, when designing a malnutrition project in Vietnam, project leaders did not spend too much time analysing why poor families in the area lacked food, but rather tried to figure out why certain very poor families actually were able to feed their children properly. The analysis aimed to uncover what strategies, even under these very dire conditions, allowed some parents to succeed when so many around them did not? What could these families have done that was so different than the majority of their communities?

As Ramlingham explains, much of the answer laid in tacit, many times unconscious patterns of behaviour which could not be readily identifiable to outside experts even if directly consulting with the locals. It was observation and inductive reasoning that exposed how some “outlying parents” supplemented meals with “less appropriate food” such as crabs or snails readily available in the rice fields, while others unintentionally developed family routines with less conventional feeding times such as more frequent even if smaller portioned meals, or for whatever reason, were more obsessive about hand hygiene[10]. Thus in this case, a complexity approach simply directed the experts to look for certain sources of information which could then be analysed through straight forward reductionist methods.

Still, rather than taking this information and translating it into new “best practice” knowledge to be modelled and taught back to the rest of the community, Jerry and Monique Sternin who ran the project, built on the natural dynamics of social systems to encourage the spread of ‘positive deviant’ behaviours. They focused on designing actions that would enable locals to better observe and emulate such behaviours through various community networks. This, as opposed to educating locals about the cause-effect relations that can explain why they should change their ways. “It’s easier to act your way into a new way of thinking rather than think your way into a new way of acting”[11]. This idea of “seeding behaviours” across different parts of the social network and building on systemic dynamics to gradually create change, has become another recurring recommendation within the current complexity related literature.

These four leading themes - taking a holistic perspective, generating information from the bottom-up, operating adaptively, and building on emerging dynamics, provide hard to dispute rules of thumb decision makers can use when trying to navigate a complex terrain. Yet they do not seem to go far enough in providing some much needed strategic guidance. While helping leaders gain a better understanding as to the complex nature of their greatest challenges, they leave them rather frustrated by the lack of a more tailored design process. Interestingly, such frustrations has been well documented by a variety of surveys suggesting how operating in complex and uncertain environments has become a leading concern for executives around the world[12].

Relieving some of these frustrations will require the development of new operational frameworks that can integrate a more detailed analysis of the manner in which social orders emerge with actual operational design. In other words, provide decision makers with a more elaborate and customisable complexity-based approach beyond the existing rules of thumb. Taking on this challenge would require a more comprehensive exploration into the meanings and opportunities for strategizing in complex environments. First and foremost, it calls for adopting a very different systemic perspective than the one taken by most complexity related publications.

4.3 The missing perspective

As the study of complex systems has been academically led and holistically focused by definition, the common perspective taken by complexity experts has tended to be one that is external to the system, being outside and looking in. Like scientists studying the evolving conditions in a petri dish, complexity researchers aimed to observe social ecologies, be them cities, economies, technologies or conflicts, so as to identify the complexity patterns that shape them. Such insights offered decision makers with great new understandings into the general laws of emergence and change within their own domain. For example - how do cities scale up[13]? Why do conflicts become protracted[14]? Or how does innovation evolve through “random walks”[15]? What they could not however do, is to directly assist decision makers when trying to manage the social and economic tensions of urban growth, working to support peace building processes, or helping develop hi-tech clusters.

Even when focusing on specific phenomena or cases, while providing valuable historical analysis of the trends, forces and tensions involved in shaping existing dynamics, such “outside looking in” analyses could never supply viable solutions. This is not simply down to the complexity of the problems and the need for any solution to address the many interdependent forces and players involved. It is also down to the fundamental lack of strategic perspective. Expert analysts could present the key systemic interplays involved, but by definition, they could never provide viable strategies for their manipulation. This is because such strategies can only be formed at the agent’s level. Ironically, the only way to form systemic / macro change is from an insider’s / micro perspective.

If reality is created through the actions taken by agents, and agents operate within a complex system, intentional efforts to alter reality can never be taken from the outside. No player can operate outside the system. His actions will always be constrained and incentivised by his own unique systemic circumstances. For example, neither Barak Obama nor Vladimir Putin could ever intervene within the Syrian crisis as “outsiders”. Their direct and indirect impact on this tragic conflict emerged long before either have considered taking any military action in the area. Consequently, the strategic choices of both will be shaped by a unique combination of political, economic, and institutional constraints and incentives. These will depend on a wide range of factors, many of which with a long and path dependent history, while others seemingly unrelated to the situation within Syria itself.

For Barak Obama for example, taking action within the Syrian system will not only depend on the internal relations between the warring factions, the shifting geographical layout of Isis, the unfolding humanitarian crisis or US relations with all its other Middle Eastern frenemies. He will also have to consider the dynamic effects any action or inaction will have on Russia’s positions, this not just in the Middle East but on various other fronts, from Ukraine to human rights. He will also consider various geo-political and economic trends involving his European allies, stability of global energy prices, and last but definitely not least, his melodramatic relations with the US Congress, other domestic flag ship policies, and the upcoming presidential election campaigns. Vladimir Putin might explore some overlapping themes, but of course from very different perspectives and needs.

For both Obama and Putin, an expert’s complexity analysis of the Syrian conflict, however comprehensive, intelligent, or insightful, can only serve as a useful input into their overall strategic design process. This is because it will never be able to integrate all the other complex patterns affecting their individual interests and leverages. For them as decision makers, it will inevitably describe the “wrong system”. Modelling the “right system” of dynamics, forces and relationships can only be generated from the decision-maker’s own perspective, i.e. from the seemingly subjective viewpoint of the player himself.

This fundamental strategic need to model a system from a decision maker’s perspective means that for all operational purposes, there are as many “Syrian systems” as the number of players involved in its underlying network. Altogether they reflect an interdependent multi-universe in which each and every player faces a unique set of circumstances, incentives, and constraints, that shape his or her own distinctive strategic choices. In ‘The Science of the Artificial’ Herbert Simon describes the environment as a detailed mould into which any good design solution must exclusively fit[16]. In the case of strategic design, the mould is the dynamic complex system, which as viewed from any player’s position across the network, is a unique one-off. The need to analyse the systemic challenge at hand requires modelling a unique complex system. This model does not aim to reflect reality in its entirety, but rather to allow the decision maker to study his or her goals, constraints, opportunities and leverages.

The strategist’s dilemma is not how to analyse a given complex system, but rather how to find potential within the complex system. Social Acupuncture therefor suggests strategic designers shift from a phenomenological to an operational mode of complexity analysis. This does not mean reducing the complexity assessed but rather looking at it with specific directives in mind. While seemingly counter intuitive, exploring complex systems from a decision-maker’s perspective can unlock a whole new space for developing innovative methods that help bridge this gap between complexity thinking and complexity doing, helping agents reclaim their agency, while hopefully also contributing to the re-coupling of science and action.

[1] UKCDS Complexity Science & International Development Workshop - 12 May 2011

[2] Warren Weaver, “Science and Complexity”, American Scientist, 36: 536 (1948)

[3] David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone, “A leader’s framework for decision making”, Harvard Business Review, Nov 2007.

[4] Elisabeth Bemiller, “We have met the enemy and he is Powerpoint”, NY Times, April 26, 2010

[5] Ben Ramlingham, Aid on the Edge of Chaos, (Oxford University Press: 2014)

[6] http://planet-tech.com/blog/las-pilas-ranch

[7] Gary Hustwit, Urbanized, http://www.hustwit.com/category/urbanized/

[8] http://www.archdaily.com/785023/elemental-releases-plans-of-4-housing-projects-for-open-source-use

[9] Aid on the edge of chaos

[10] Ramlingham, Aid on the Edge of Chaos, pp272-276

[11] Ibid p275

[12] Corporate Learning Priorities Survey 2015 – Henley Business School, http://www.henley.ac.uk/files/pdf/exec-ed/2015_Corporate_Learning_Survery.pdf; Management Tools and Trends 2015 – Bain, http://www.bain.com/publications/articles/management-tools-and-trends-2015.aspx; Confronting Complexity KPMG 2010 - https://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/Documents/complexity-research-report.pdf;

[13] Jeffrey West, The Surprising Math of Cities, https://www.ted.com/talks/geoffrey_west_the_surprising_math_of_cities_and_corporations

[14] Peter Coleman, The Five Percent – finding solutions to seemingly impossible conflicts, (NY, Public Affairs: 2011)

[15] Brain Arthur, The Nature of Technology – what it is and how it evolves, (Penguin: 2009); and Eric Beinhocker, The Origin of Wealth – complexity and the radical remaking of economics, (Random House: 2007)

[16] Herbert A. Simon, Science of the Artificial, (MIT Press: 1996)